Administrative authority refers to the powers exercised by government bodies, officials, and agencies to implement laws, make decisions, and manage public affairs.[1] In Bharat, this area of law has evolved significantly through the Supreme Court’s interpretations, ensuring that such powers are not arbitrary but aligned with constitutional principles like fairness, equality, and justice.[2] For law students and personnel, grasping these doctrines is essential as they form the backbone of judicial review, helping to check executive overreach and protect citizens’ rights. Even for government employees, understanding of this subject is must as it is their job to serve the people of this nation as per the constitutional and statutory provisions. This article explores the major doctrines shaping administrative authority, drawing from landmark Supreme Court judgments, in a way that highlights their practical implications and historical development.

Principles of Natural Justice: The Foundation of Fair Administrative Decisions

The principles of natural justice are fundamental rules that ensure fairness in administrative proceedings, even when statutes do not explicitly require them. These principles, rooted in common sense and equity, mandate that no one should be condemned without a fair hearing and that decisions must be made impartially. In Bharatiya administrative law, the Supreme Court has expanded these principles to apply to a wide range of actions, from disciplinary proceedings to licensing decisions, emphasizing that they humanize the law and prevent miscarriages of justice. For instance, the principle of audi alteram partem, meaning “hear the other side,” requires authorities to give affected parties an opportunity to present their case, while nemo judex in causa sua, or “no one should be a judge in their own cause,” guards against bias.

One of the pivotal judgments illustrating this is A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India[3], where the Supreme Court held that natural justice applies to administrative actions, not just judicial ones. In this case, a selection board for forest services included a candidate’s superior, raising concerns of bias, and the Court quashed the selection, stressing that fairness must permeate all decision-making processes. Another landmark is Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India[4], which revolutionized administrative law by linking natural justice to Article 21’s right to life and liberty. Here, the passport impoundment without a hearing was deemed unfair, expanding “procedure established by law” to include just and reasonable processes. One should note how these cases shifted focus from rigid statutory compliance to substantive fairness, influencing countless subsequent rulings and reinforcing that administrative authority must always prioritize equity to avoid arbitrariness.

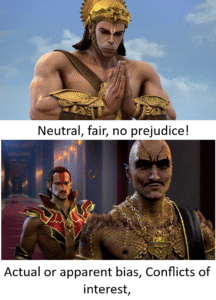

The Doctrine of Bias: Safeguarding Impartiality in Administrative Actions

The doctrine of bias, a key component of natural justice, ensures that decision-makers remain neutral and free from any personal, financial, or official prejudices that could influence their judgments. In administrative law, bias can be actual or apparent, and even the likelihood of it can invalidate a decision, as justice must not only be done but seen to be done. This doctrine prevents conflicts of interest, promoting public trust in administrative bodies. The Supreme Court has categorized bias into types like personal, pecuniary, and official, applying strict scrutiny to uphold Article 14’s equality mandate.

A classic example is Gullapalli Nageswara Rao v. State of Andhra Pradesh[5], where the Court addressed official bias in a transport nationalization scheme. The Transport Minister, who had preconceived views, heard objections, leading the Court to set aside the decision because it violated the rule that no one should judge their own cause. Similarly, in A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India, the involvement of an interested party on the selection board was ruled biased, extending the doctrine to quasi-judicial functions. For lawyers, law makers and administrative officers, these judgments demonstrate how the Supreme Court uses this doctrine to dismantle unfair administrative structures, teaching that even subtle biases can undermine authority and that thorough inquiries into allegations of bias are crucial for procedural integrity.

Doctrine of Ultra Vires: Boundaries of Administrative Power

The doctrine of ultra vires, meaning “beyond powers,” acts as a critical check on administrative authority by declaring any action exceeding the legal limits void. This includes substantive ultra vires, where the action goes beyond the parent statute’s scope, and procedural ultra vires, where required processes are ignored. In Bharat, the Supreme Court employs this doctrine during judicial review to ensure delegated powers are exercised within constitutional and statutory confines, preventing abuse and maintaining the rule of law.

A significant judgment is Ajoy Kumar Mukherjee v. Union of India[6], where the Court struck down delegated legislation that narrowed the parent act’s scope, affirming that subordinates cannot overstep enabling provisions. Another key case is Air India v. Nergesh Meerza[7], where regulations discriminating against air hostesses on marriage grounds were held ultra vires Article 14 for being arbitrary. Law personnel will find this doctrine particularly insightful as it underscores the hierarchy of laws, showing how the Supreme Court intervenes to invalidate overreaching administrative rules, thus balancing executive efficiency with legal accountability and protecting individual rights from unchecked power.

Wednesbury Principle of Unreasonableness: Testing Rationality in Decisions

The Wednesbury principle, derived from the English case Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd. v. Wednesbury Corporation[8], tests administrative decisions for unreasonableness so extreme that no sensible authority could have arrived at them. Adopted in Bharat, it serves as a ground for judicial review, focusing on the decision-making process rather than the outcome, to curb irrationality without courts substituting their own views.

The Supreme Court applied this in Tata Cellular v. Union of India[9], reviewing a telecom tender award and holding that decisions must not defy logic or moral standards, though courts should not re-evaluate merits. In Union of India v. G. Ganayutham[10], the Court clarified that Wednesbury applies to ordinary administrative actions, while proportionality suits fundamental rights infringements. This principle appeals that by illustrating the delicate balance in judicial oversight, teaching that while administrative discretion is broad, it must remain grounded in reason, and offering tools to challenge opaque or absurd governmental choices in practice.

Doctrine of Proportionality: Ensuring Balanced Administrative Measures

The doctrine of proportionality requires that administrative actions be proportionate to their objectives, meaning the means employed should not be more restrictive than necessary. Introduced in Bharat as an advancement over Wednesbury, it involves a structured test of suitability, necessity, and balancing, ensuring minimal infringement on rights. The Supreme Court accepted it, applying it particularly in cases involving punishments or rights violations.

In Om Kumar v. Union of India[11], the Court formalized the doctrine for reviewing disciplinary penalties, stating that actions must balance individual rights with public interest without excess. Ranjit Thakur v. Union of India[12] earlier hinted at it by quashing an irrational court-martial sentence. This doctrine is a modern tool for nuanced analysis, highlighting how the Court adapts global standards to Bharatiya contexts, encouraging critical evaluation of whether administrative sanctions are fair or disproportionately harsh in real-world scenarios.

Doctrine of Legitimate Expectation: Upholding Promises and Fairness

The doctrine of legitimate expectation protects individuals’ reasonable expectations arising from government promises, policies, or consistent practices, even without enforceable rights. It compels authorities to act fairly, providing relief if expectations are dashed without justification, rooted in Article 14’s anti-arbitrariness.

The Supreme Court elaborated this in Food Corporation of India v. Kamdhenu Cattle Feed Industries[13], where denying a tender despite highest bid violated expectations of fair consideration. In State of Kerala v. K.G. Madhavan Pillai[14], a school sanction created expectations quashed by a sudden abeyance order without hearing. This doctrine bridges estoppel and fairness, empowering challenges to policy flip-flops and fostering accountable governance through judicial enforcement of trust in public administration.

The Doctrine of Exhaustion of Alternative Remedies: Promoting Efficient Justice

This doctrine requires individuals to pursue statutory remedies before approaching courts via writs, preventing premature judicial interference and respecting legislative intent. It ensures administrative disputes are resolved at lower levels first, but exceptions exist for fundamental rights violations or jurisdictional errors.

In a recent judgment, the Supreme Court in cases like the one referenced in high court interventions emphasized that writ jurisdiction should not bypass adequate alternatives. This teaches strategic litigation, balancing access to justice with system efficiency, and understanding when extraordinary remedies are warranted despite available options.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Role of Supreme Court in Shaping Administrative Authority

Through these doctrines and judgments, the Supreme Court has transformed administrative authority from unchecked power to an accountable framework, aligning it with constitutional values. For law students, law professionals and even for government employees, studying these provides not just theoretical knowledge but practical insights into advocating for justice, as the Court’s evolving jurisprudence continues to adapt to modern challenges like digital governance and policy complexities.

References:

[1] “An Introduction to Public Administration”, Mumbai University Study Material.

[2] “The Doctrine Of “Manifest Arbitrariness” – A Critique” by Eklavya Dwivedi, available at https://www.indialawjournal.org/the-doctrine-of-manifest-arbitrariness.php#:~:text=%E2%80%9Cequality%20is%20antithetical%20to%20arbitrariness,(not%20so)%20proper%20growth.

[3] A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India [AIR 1970 SUPREME COURT 150]

[4] Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India [1978 SCR (2) 621]

[5] Gullapalli Nageswara Rao v. State of Andhra Pradesh [1958 ANDHLT 1014]

[6] Ajoy Kumar Mukherjee v. Union of India, [(1984) 2 SERVLR 50]

[7] Air India v. Nergesh Meerza [(1981) 2 LABLJ 314]

[8] “Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd. v. Wednesbury Corporation”, Aiswarya Agrawal, Law Bhoomi available at: https://lawbhoomi.com/associated-provincial-picture-houses-ltd-v-wednesbury-corporation/

[9] Tata Cellular v. Union of India [(1996) 1 BANKCLR 1]

[10] Union of India v. G. Ganayutham [(2000) 2 LABLJ 648]

[11] Om Kumar v. Union of India [2001 SCC (L&S) 1039]

[12] Ranjit Thakur v. Union of India [(1987) PAT LJR 79]

[13] Food Corporation of India v. Kamdhenu Cattle Feed Industries [1992(3) SCALE 85]

[14] State of Kerala v. K.G. Madhavan Pillai [4 SCC 669]