2.1 Preamble:

2.1.1 Bare Act Text:

THE ANCIENT MONUMENTS AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES AND REMAINS ACT, 1958

ACT NO. 24 OF 19581 [28th August, 1958.]

An Act to provide for the preservation of ancient and historical monuments and archaeological sites and remains of national importance, for the regulation of archaeological excavations and for the protection of sculptures, carvings and other like objects.

BE it enacted by Parliament in the Ninth Year of the Republic of India as follows:―

Footnote in bare Act

Extended to Goa, Daman and Diu with modifications by Reg. 12 of 1962, S. 3 and Sch. (w.e.f. 22-11-1962). Extended to Dadra and Nagar Haveli by Reg. 6 of 1963, s. 2 and Sch. I (w.e.f. 11-7-1965) and Pondicherry by Reg. 7 of 1963, s. 3 and Sch. I (w.e.f. 1-10-1963).

2.1.2 Explanation:

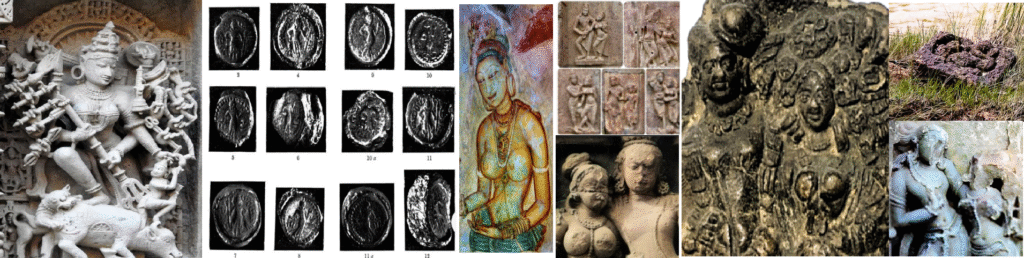

The preamble of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958 (AMASR Act) is like the opening scene of an epic movie about Bharat’s rich heritage. It declares the Act’s mission to protect and preserve ancient monuments, archaeological sites, and precious artifacts like sculptures and carvings that are of national importance. Enacted in 1958, in the “Ninth Year of the Republic of India,” it reflects a young nation’s determination to safeguard its cultural treasures, e.g. majestic forts, ancient temples, or hidden cave inscriptions that have stood for over a century. The preamble sets three clear goals: firstly to preserve historical monuments and sites, secondly to regulate archaeological digs to prevent haphazard treasure hunts, and finally to protect detachable artifacts like coins or manuscripts from theft or damage.[1] It’s a promise to keep Bharat’s past alive for future generations, balancing cultural pride with public access.

This preamble operates on the doctrine of public trust, meaning the government holds these cultural assets in trust for the people, ensuring they’re not destroyed by neglect or modern development.[2] It also embodies the doctrine of parens patriae, where the state acts as a guardian to protect heritage that defines Bharat’s identity, much like a parent caring for a child.[3] Additionally, the doctrine of sustainable development subtly applies, as the Act seeks to harmonize preservation with modern needs, like allowing limited public works near monuments (as seen in later sections like 20A).[4] These doctrines ensure the Act isn’t just about locking away history but making it accessible and relevant while protecting it from harm.

The mention of regulating excavations hints at preventing looting ensuring only trained archaeologists unearth history.[5] The Act’s scope, covering the entire country (amended in 1972 to include all states), shows a unified national effort to cherish heritage, making it a shared responsibility.

References:

[1] “The Ancient Monuments And Archaeological Sites And Remains Act, 1958 – Statement of Objects and Reasons, Indian Kanoon, available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/981642/, Last visited on Dt. 17.07.2025.

[2] Public Trust Doctrine, Manupatra Academy, available at https://www.manupatracademy.com/legalpost/public-trust-doctrine, Last visited on Dt. 17.07.2025

[3] “Doctrine of Parens Patriae”, Juris Centre, Dt. 10.5.2021, available at https://juriscentre.com/2021/05/10/doctrine-of-parens-patriae/, Last visited on Dt. 17.07.2025

[4] Narmada Bachao Andolan vs Union Of India And Others, [AIR 2000 SUPREME COURT 3751]

[5] National Policy on Archaeological Exploration and Excavation, Archaeological Survey Of India

Image credit: https://x.com/GemsOfINDOLOGY