The Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of 1904 (1904 Act), ostensibly a landmark in safeguarding Bharat’s ancient heritage, exemplifies the duplicitous nature of colonial policies, cloaked in benevolence while serving the machinery of empire. Enacted under Viceroy Lord Curzon’s administration, this legislation empowered the British-controlled Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to declare monuments of “historical or architectural interest” as protected, ostensibly to curb looting, vandalism, and neglect. Yet, beneath this veneer of stewardship lay a profoundly extractive and paternalistic agenda, the Act facilitated the systematic appropriation of Bharat’s cultural treasures, transforming sacred sites into trophies of imperial conquest.[1]

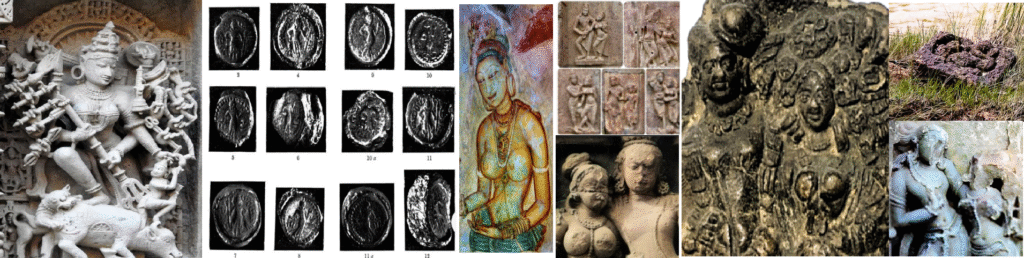

Critics, including postcolonial scholars like Tapati Guha-Thakurta, argue that the 1904 Act was less about genuine preservation and more about asserting British superiority over “backward” indigenous custodianship. Local communities, often temple priests, villagers, or landowners, were dispossessed of traditional rights to maintain or access sites, reclassified as “ownerless” relics under state control. The ASI’s authority to regulate excavations, restrict repairs, and even demolish “encroachments” prioritized European antiquarian tastes, favoring grand ruins like the Taj Mahal or Ajanta Caves while marginalizing living cultural practices. Artifacts were routinely shipped to British museums, such as the Victoria Memorial or the British Museum, under the guise of “scientific study,” perpetuating a narrative of Bharat as a passive repository of history rather than an active cultural continuum.[2]

Moreover, the Act’s enforcement was selective and hypocritical, e.g. colonial infrastructure projects, railways, and plantations routinely razed monuments without repercussions, while penalties targeted Bharatiya “trespassers.” This reflected Orientalist biases, where preservation justified land grabs and cultural erasure, aligning with broader policies of divide-and-rule. The 1904 Act’s legacy, critiqued as “archaeological imperialism,” set a contentious precedent, influencing the postcolonial AMASR Act of 1958, which inherited its framework but struggled to decolonize its Eurocentric biases. Unpacking this history reveals how colonial “preservation” entrenched power imbalances, underscoring the need to reclaim heritage narratives from imperial distortions. Let us find out how 1904 Act influenced AMASR Act and still causing mismanagement of ancient sites specifically related to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Sikh and Tribal history and religious sentiments. Hereinafter all these groups are called Sanatanis collectively.

[1] “Manual of Conservation and Restoration of Monuments” Dr. R. Kannan, Government Museum, Chennai, 2007

[2] “’Our Gods, Their Museums’: The Contrary Careers Of India’s Art Objects”, Tapati Guha-Thakurta, conference at the Department of Art History of the University of Nottingham in January 2007